How They're Doing: Minnesotans on Pro Tour Money Lists -- April 22

April 22, 2024

Minnesota’s 600-plus golf courses, past and present, have taken up residence just about everywhere: mounted on hilltops, perched alongside lakes, rooted next to rivers, cozied up to cul-de-sacs, flanked by forests, put out to pastures and deserted on islands.

Wait, what? Say that last part again. A Minnesota golf course on an island? It’s unheard of.

Yep, pretty much.

In 130 years of organized Minnesota golf, in a state that accommodates more than 10,000 lakes, the all-time count of island courses appears to be a mere two—both born exactly a century ago and both long gone.

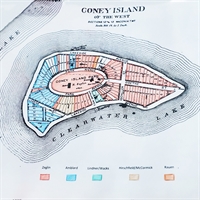

Coney Isle Golf Course

On a September morning in 2023, a dozen curiosity-seekers set off by boat at Lake Waconia Regional Park, their destination a mile away: a landing on the southwestern tip of Coney Island of the West. (Theories vary as to the origin of the name; it also was known as Paradise Island in the early 1900s.) The 31-acre island as a whole was the excursion’s main attraction, and only one visitor had a particular interest in what once lay near its eastern shore. (This is called fore-shadowing; please excuse the pun.)

It’s a fascinating place, beyond its thick woods, winding trails and the bucolic backdrop of the city of Waconia, prominently in view a half-mile away. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, Coney Island of the West holds archeological and historical significance.

Indigenous people visited the island for centuries before it was settled by those of European descent, and relics are still found there. Lambert Naegele bought the island in 1884, platted it with streets named after German authors such as Goethe and built a large hotel. Plots of land were sold. Private cabins were built.

Reinhold Zeglin and his sons operated the island resort before the turn of the 20th century. The Zeglins’ interests focused on sports; they built a bowling alley, added croquet grounds and hosted the University of Minnesota football team for preseason training from 1903 to 1905. Workouts were held on a small, flat, open patch on the eastern end of the island.

“[A] better spot could not be found if the world was raked with a fine-toothed comb,” the Minneapolis Journal declared of Coney Island in August 1904.

Two decades later, J.W. Zeglin invited sportsmen of a different bent to play a burgeoning game on the grounds. “Coney Isle Hotel / Open season May 1924 on May 29th,” began an ad in the Minneapolis Tribune. “Under same management for

36 years.”

The former “golf course” is about the size of a football field, not coincidentally, and not much more. It’s reasonable to imagine a longest hole of about 130 yards, a couple more of 75 to 80, and one or two others that are pitch-and-putt. That’s if you stretch it.

Zeglin spread word about his golf course. In addition to Minneapolis papers, Coney Island was advertised in newspapers in Kansas City, Omaha and Bartlesville, Oklahoma. (The latter’s ad inexplicably said the island was 130 miles from the Twin Cities). An Omaha Evening World-Herald ad boasted that, based on service, atmosphere and location, Coney Isle was “in a class by itself for real merit.”

But as a golf course, Coney Isle was small potatoes—a handful at best. After the five-hole reference in 1924, a Minneapolis Journal story in 1925 referred to “a four-hole golf course, located on the island.” And then in 1928, a Journal description had reduced the grounds to a “four-hole putting course.”

That was the last reference I could find to golf on Coney Island.

The island’s popularity had peaked before that, and even though a dance hall, restaurant and more cabins were added starting in 1940, things were left to deteriorate. Vandalism contributed to further degeneration until efforts to revitalize began in 1975. Today, Carver County continues revitalization, with picnic grounds, trails, beaches and a boat launch, with plans for more.

Circle Island Golf Course

In the exact months J.W. Zeglin was starting something small on one island, Graham Sharman was planning something very big on another.

Sharman was president of Sharman & Cross, a Minneapolis real estate and investment firm. On March 5, 1924, the Faribault Journal ran a story headlined “WILL ESTABLISH BIG RESORT.”

The story began: “The firm of Sharman & Cross, of Minneapolis, have announced that they will construct a $100,000 summer resort in Rice County this year, work to begin just as soon as the frost is out of the ground ...”

Culling from newspaper accounts, the project’s features would include a hotel, cabins, playground, tennis courts, concert pavilion, waterslide, boathouse, ferries and—the centerpiece—an 18-hole island golf course.

“... Rice County,” the Journal story continued, “is assured of the finest summer resort in Southern Minnesota.” Of course, time would be the judge of that.

Weeks before the Journal story was published, Caroline Dulac had, for $40,000, sold 130 acres of land that had been in her family since the previous century. The tract consisted of a 100-acre island on Circle Lake and 30 acres adjoining the lake’s eastern shore.

Circle Lake, not terribly circular, lies 8 miles north of Faribault, 9 miles southwest of Northfield and 40 miles south of Minneapolis. As golf’s popularity boomed in the early 1920s, Sharman no doubt considered demographics and seized an opportunity.

Sharman and his business partner Thomas Cross promoted their project with ads in Minneapolis and Faribault newspapers, and composed large, detailed announcements touting the newly named Circle Island Golf Course. The copy writers heaped on hyperbole and breached a border into bombast.

“Fore!!!” blared one ad featuring a map showing Circle Lake and its proximity to Minnesota cities. “A frolicking swim in the sparkling water on your own sandy beach ... An hour’s boating with gamey fish beneath, daring you to drop your line ... Back to rest under your own maples or to stroll in the woods, but wait—a hundred steps away—the Golf Course—YOUR Golf Course. Oh Boy! Perhaps a hole in one, at least a birdie; anyway it’s a grand old game.”

Sharman’s company consistently made outlandish claims. Principally, suggestions of an 18-hole course were half-baked. The island didn’t have nearly enough room for 18 palatable holes, not to mention room to also accommodate the 249 residential lots, most of them 50 by 150 feet, that were platted around the island’s perimeter.

Yet the project was launched. Work on a course, scaled down to nine holes, began in mid-April 1924. “A well-known golf course architect has the course under construction,” a Sharman & Cross ad read in part. “The course covers the center of the island and has been pronounced the best natural course in the Midwest.” (The architect was not identified and remains unknown.)

The Circle Island routing looks legit. Using Google Maps and an ad that delineated tees and greens, hole lengths can be estimated. The interior of the island had been clear-cut decades before, and the course likely measured close to 2,500 yards. The first hole, accessed after a ferry ride, would have headed south about 293 yards. The fourth was probably the longest hole, close to 500 yards.

The course opened before summer broke in 1924. Newspapers carried scant coverage of the course, but there were reports on events at the “resort” (sans hotel, cottages and accoutrements). A Theopold-Reid Co. picnic drew more than 100 visitors, and a summer Farm Bureau picnic drew 7,500, the Minneapolis Journal reported. A team from Faribault defeated one from Northfield in the first competition at the golf course.

In March 1924, Sharman said it would take two to three years for the resort to be completed. A century later, it still isn’t—and it was barely ever started. A dance pavilion on the “mainland” 30 acres was built and proved popular before burning down in 1938. The island, meanwhile, lay almost untouched except for nine greens and nine concrete golf cups, one of which was unearthed by Shawn Nugent, who owned the island in the late 1980s and now operates a business on Circle Lake’s eastern shore.

Despite reports of flocks of visitors, it’s a mystery as to whether Sharman ever persuaded a client to purchase a lot on Circle Island. Dennis Henry, a retired Gustavus Adolphus physics professor, spent a few summers in the 1950s helping farm the island with his uncle Herb Younker, who owned it. Duties included ferrying cattle across the lake. Henry’s recollection was that there was only one building on the island, a tiled house with poured concrete floors. He remembered airplanes landing on the island, and “it was amazing how little the trees had encroached on the area.” Nugent said the island is largely overgrown now. It was, for a time in late 2023, listed online as being for sale, with an asking price of $1,030,000.

The Circle Island Golf mystery is further complicated by how long—or how short—the course operations lasted. A 1958 paper held by the Rice County Historical Society declared that “during the depression, the resort quieted to nothing.” A 1999 newspaper story was headlined “Depression kills island course,” but offered no supporting evidence of the timeline.

It’s more likely the course was abandoned before 1930. A Faribault News ad from 1926 promoted a three-day Fourth of July celebration, including golf. But after that ... nothing. Reviews of area newspapers from 1927-1930 produced no evidence the course was still in play.

Whether the demise of the Circle Island project qualifies as tragedy is arguable. After all, close to 250 other Minnesota golf courses have similarly been abandoned.

As for actual tragedy ... Henry remembers that one summer, an independent-minded steer was among cattle ferried to the island for summer vacation. It made a break for freedom by starting a swim back to the mainland.

“That steer had been a problem,” Henry says.

A phone call from a neighbor on the mainland followed. “You’d better come get your steer,” the neighbor said. “Because it’s floating in the lake, belly up.” It had been struck by lightning.

When it was suggested the steer deserved credit for ingenuity, Henry retorted, “It got its comeuppance.”

Contact Us

Have a question about the Minnesota Golf Association, your MGA membership or the contents of this website? Let us help.